Are you struggling to choose the right manufacturing method or understand why sheet metal forming is so widely used across industries? Misunderstanding processes, materials, and design rules can lead to costly errors, weak parts, or production delays. This in-depth blog breaks down sheet metal forming clearly and practically, from core processes to real-world applications, so that you can make confident technical and sourcing decisions. Read on to master the fundamentals and avoid common pitfalls.

What Is Sheet Metal Forming?

Sheet metal forming is an industrial manufacturing process in which mechanical force is applied to thin metal sheets (typically 0.005-0.25 inches thick) to produce plastic deformation, reshaping them into functional or decorative components. As a key part of sheet metal fabrication, the process uses press brakes, punches, and dies to form materials such as steel, aluminum, and copper, relying on their ductility rather than material removal. Unlike cutting or machining, sheet metal forming preserves structural integrity while enabling the creation of precise shapes for various applications, including automotive, aerospace, construction, and industry.

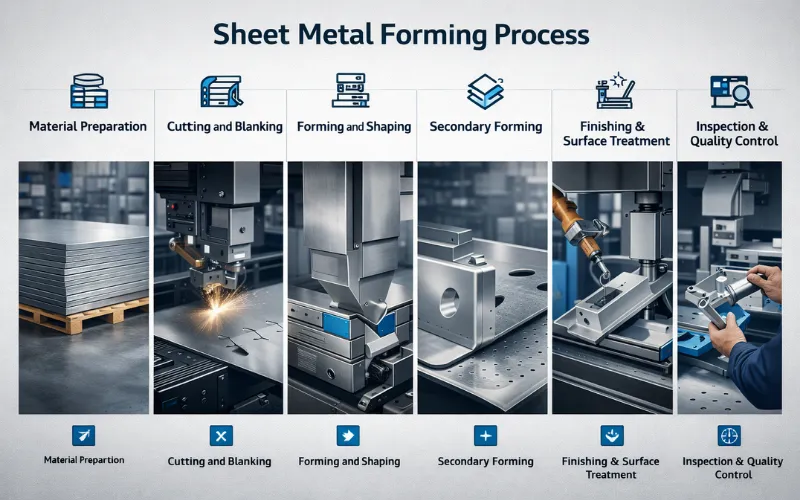

How Does Sheet Metal Forming Work?

Sheet metal forming works by applying controlled mechanical force to flat metal sheets, causing permanent (plastic) deformation without removing material. While the fundamental principle has remained the same for decades, modern sheet metal forming relies heavily on CNC-controlled equipment, digital simulation, and process monitoring to improve accuracy, reduce defects, and shorten production cycles. Understanding each stage of the forming workflow helps designers and manufacturers optimize quality, cost, and efficiency.

Material Selection and Preparation

The process begins with selecting the appropriate material and thickness based on mechanical requirements, formability, corrosion resistance, and cost. Modern manufacturers increasingly consider not only strength but also springback behavior and sustainability factors when choosing materials. Key points in material preparation:

- Material grade and temper directly influence formability and the risk of defects.

- Sheet thickness affects the required forming force and achievable bend radii.

- Surface condition and coatings impact friction and tool wear.

- Sheets are commonly supplied in coils and flattened before processing.

- Material data is often validated using supplier datasheets and digital material models.

Cutting and Blanking

Before forming, the metal sheet is cut into a specific shape known as a blank. Advances in cutting technology have improved accuracy and reduced material waste. Key points in cutting and blanking:

- Laser cutting provides high precision and design flexibility.

- Punching and shearing offer fast cycle times for high-volume production.

- Blank geometry is critical for controlling material flow during forming.

- Modern nesting software optimizes sheet usage and reduces scrap.

- Clean-cut edges help prevent crack initiation during forming.

Forming and Shaping Operations

This is the core stage where the metal sheet is reshaped into its final or near-final geometry. The forming force is applied using presses, rollers, or hydraulic systems, depending on the chosen process. Key points in forming operations:

- CNC press brakes and stamping presses apply controlled force.

- Tool geometry determines bend angle, radius, and final shape.

- Material undergoes plastic deformation beyond its yield point.

- Springback is predicted and compensated through software or tooling adjustments.

- Forming simulations are increasingly used to reduce trial-and-error.

Secondary Forming and Feature Creation

After the main forming step, additional operations may be required to add functional or assembly-related features. These steps refine the part and improve usability. Some important points:

- Piercing creates holes for fasteners or ventilation.

- Flanging strengthens edges and improves safety.

- Embossing adds stiffness or branding details.

- Progressive dies can perform multiple steps in one press cycle.

- Automation reduces handling errors and improves consistency.

Finishing and Surface Treatment

Once the desired shape is achieved, surface finishing may be applied to improve appearance, corrosion resistance, or durability. Key points in finishing:

- Common treatments include powder coating, anodizing, and plating.

- Surface finishing can affect dimensional tolerances.

- Cleaning removes forming lubricants and residues.

- Coatings are selected based on environmental exposure and performance needs.

- Environmental regulations increasingly influence finishing choices.

Inspection and Quality Control

Quality control ensures that formed parts meet design specifications and performance requirements. Modern inspection methods combine traditional measurement with digital tools. Some highlights of this step you should remember:

- Dimensional checks verify angles, radii, and flatness.

- Visual inspection identifies cracks, wrinkles, or surface defects.

- Automated inspection systems improve speed and repeatability.

- Statistical process control helps maintain consistency in high-volume production.

- Data-driven monitoring supports continuous process improvement.

Common Sheet Metal Forming Techniques

Sheet metal forming includes a wide range of techniques, each suited to specific shapes, production volumes, and material properties. Below are the most widely used and industrially important methods.

Bending

Bending is one of the simplest and most common sheet metal forming techniques. It involves applying force to a sheet to create a straight-line deformation, resulting in an angle or curved shape. In bending, the sheet is placed over a die and pressed by a punch. As force increases, the material yields and bends around the die radius. A key concept in bending is springback, which occurs when the material elastically recovers slightly after the force is removed. Common bending methods include:

- Air bending: The sheet contacts only the punch tip and die shoulders, offering flexibility and lower tooling cost.

- Bottom bending: The sheet is pressed firmly into the die, improving accuracy.

- Coining: High force is applied to eliminate springback and achieve precise angles.

Bending is widely used for brackets, enclosures, frames, and structural components.

Deep Drawing

Deep drawing is a forming process used to create hollow or cup-shaped parts from flat sheet metal. Unlike bending, which deforms the material along a line, deep drawing redistributes material across a larger area. In this process, a punch pushes the sheet into a die cavity while a blank holder controls material flow and prevents wrinkling. The ratio between the blank diameter and the final part diameter (known as the draw ratio) is a critical design parameter. Deep drawing is commonly used for:

- Beverage cans

- Automotive fuel tanks

- Kitchen sinks

- Medical containers

Its main advantage is the ability to produce seamless, strong parts with excellent surface quality.

Roll Forming

Roll forming is a continuous forming process in which a metal strip passes through a series of rotating rolls. Each set of rolls incrementally bends the sheet until the desired cross-sectional profile is achieved. Unlike stamping or bending, roll forming is ideal for producing long, uniform parts with consistent cross-sections, such as:

- Structural channels

- Roofing panels

- Automotive rails

- Door frame

Roll forming offers high production speed, excellent dimensional consistency, and minimal material waste, making it highly suitable for large-scale manufacturing.

Stamping and Punching

Stamping is a broad term that covers several sheet metal operations performed using a press and die set. Punching and blanking are two closely related stamping processes.

- Punching removes material from the sheet to create holes or cutouts.

- Blanking cuts a part’s outer profile from the sheet.

Stamping can also include embossing, coining, and forming operations performed in a single press stroke. These processes are highly efficient for high-volume production and are widely used in automotive, electronics, and appliance manufacturing.

Hydroforming

Hydroforming uses high-pressure fluid, typically water or oil, to shape sheet metal against a die. Instead of a solid punch, fluid pressure evenly distributes force across the material, allowing more complex shapes and smoother surfaces. Advantages of hydroforming include:

- Reduced risk of wrinkling or tearing

- Improved material distribution

- Ability to form complex geometries

Hydroforming is commonly used in automotive and aerospace applications where lightweight yet strong components are required.

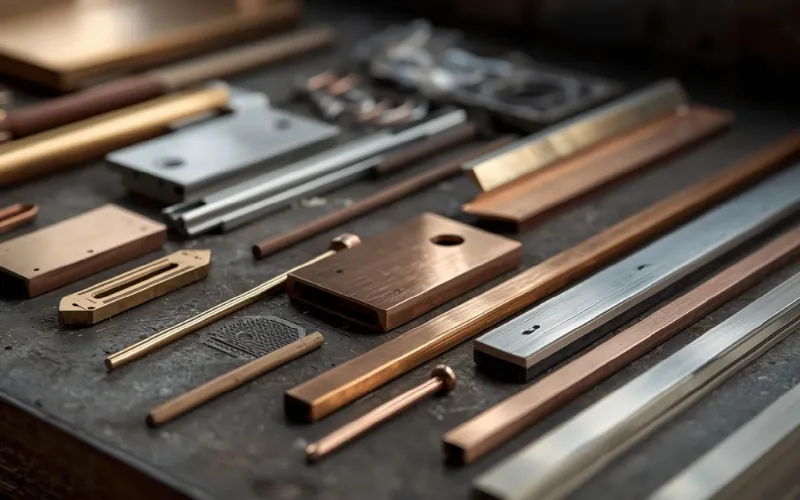

What Materials Are Used In Sheet Metal Forming?

Material selection plays a crucial role in sheet metal forming success. Different metals respond differently to forming forces, and their mechanical properties directly affect formability, strength, and final performance.

Steel (Carbon Steel and Stainless Steel)

Steel remains the most widely used material in sheet metal forming due to its strength, availability, and cost efficiency. Carbon steels are especially popular for structural and general-purpose components, while stainless steels are chosen for corrosion resistance and aesthetics. Key characteristics of steel in sheet metal forming:

- Good overall formability, especially in low-carbon grades

- High strength and stiffness suitable for structural components

- Moderate to high springback, particularly in stainless steel

- Wide availability and cost efficiency for mass production

- Compatible with bending, stamping, deep drawing, and roll forming

Aluminum

Aluminum is widely used where weight reduction and corrosion resistance are priorities. Advances in aluminum alloy design have significantly improved formability, making aluminum more competitive with steel in many applications. Key characteristics of aluminum in sheet metal forming:

- Low density, enabling significant weight savings

- Good corrosion resistance without additional coatings

- Higher springback than steel, requiring compensation in tooling

- Good formability in non-heat-treated or soft tempers

- Commonly used in automotive, aerospace, and electronics applications

Copper

Copper is primarily used in sheet metal forming when electrical conductivity, thermal performance, or corrosion resistance is required. Although less common than steel or aluminum, copper plays a critical role in electronics and energy-related applications. Some key characteristics of copper in sheet metal forming:

- Excellent ductility, making it easy to form at room temperature

- Very high electrical and thermal conductivity

- Low forming force requirements due to low yield strength

- Rapid work hardening, which can limit complex multi-stage forming

- Sensitive surface that requires careful handling to avoid damage

Brass

Brass, an alloy of copper and zinc, is often selected for its balance of formability, corrosion resistance, and appearance. It is commonly used in decorative, architectural, and precision components. Its key characteristics:

- Better strength than copper while maintaining good ductility

- Smooth surface finish with strong aesthetic appeal

- Low risk of cracking during bending and drawing

- Good corrosion resistance in many environments

- Higher material cost compared to steel and aluminum

Titanium

Titanium is used in sheet metal forming for high-performance applications where strength, corrosion resistance, and low weight are critical. While difficult to form, modern forming techniques have expanded their industrial use.

Key characteristics of titanium in sheet metal forming:

- Exceptional strength-to-weight ratio

- Outstanding corrosion resistance in harsh environments

- Limited room-temperature formability compared to other metals

- Often requires warm or hot forming to reduce cracking risk

- High material and processing costs, suited for specialized industries

Sheet Metal Forming vs Other Manufacturing Methods

Choosing the right manufacturing method has a direct impact on cost, production efficiency, and part performance. The table below compares sheet metal forming with other common manufacturing processes to help you quickly determine which method best fits your design and production needs.

| Sheet Metal Forming | Machining | Casting | Extrusion | |

| Material Usage | Very efficient, minimal waste | High material waste due to cutting | Moderate waste (gates, risers) | Efficient, but limited to specific profiles |

| Part Thickness | Thin to medium thickness | Any thickness | Medium to thick sections | Constant cross-section only |

| Geometric Complexity | Medium to high (with tooling limits) | Very high, complex 3D shapes | Very high, complex shapes | Limited to uniform cross-sections |

| Mechanical Properties | Depends on the material and process | Good strength along the extrusion direction | Lower due to internal porosity | Good strength along extrusion direction |

| Surface Finish | Good, consistent | Excellent | Moderate, may require finishing | Good |

| Dimensional Accuracy | High, especially in bending and stamping | Very high | Moderate | High in cross-section only |

| Tooling Cost | High initial cost, low per-part cost | Low tooling, high per-part cost | High tooling cost | High tooling cost |

| Production Volume | Medium to very high | Low to medium | Medium to high | High |

| Lead Time | Short once tooling is ready | Short for prototypes | Longer due to mold preparation | Medium |

| Typical Applications | Enclosures, panels, brackets, frames | Precision components, prototypes | Engine blocks, housings | Profiles, rails, heat sinks |

| Cost Effectiveness | Best for repeat production | Best for low volume or custom parts | Best for complex thick parts | Best for long uniform parts |

Conclusion

Sheet metal forming is a cornerstone of modern manufacturing, offering an efficient, versatile, and scalable way to produce high-quality metal components. By understanding the processes, materials, advantages, limitations, and design principles involved, manufacturers and engineers can make informed decisions that optimize performance, cost, and reliability. Whether for mass production or specialized applications, sheet metal forming remains an indispensable technology across industries.

FAQs

Sheet metal forming specifically deals with thin metal sheets, while metal forming also includes bulk processes like forging and extrusion.

Tooling costs can be high initially, but the process is very cost-effective for medium to high production volumes.

Sheet metal typically ranges from about 0.5 mm to 6 mm in thickness, depending on the application.